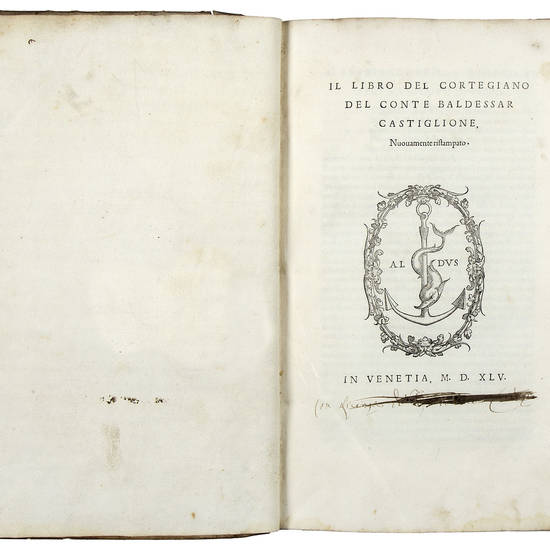

Folio (315x212 mm). [122] leaves. Collation: *4 a-o8 p6. Aldine device on title page and last leaf verso. Register and colophon on l. p5v. Contemporary flexible vellum with overlapping edges, inked title on spine (slightly stained, minor losses to spine and panels, traces of ties). The letter “Z” handwritten on the front panel and flyleaf. Ownership inscription on title page, partly inked out and barely readable. Loss to upper outer corner affecting the front panel and roughly one third of the volume. An unsophisticated and genuine copy with wide margins.

SECOND ALDINE FOLIO EDITION (fourth Aldine overall) after the princeps of 1528, of which the present is a reprint, and the following 8vo editions of 1533 and 1541.

The work had a long history before coming to print. First composed at the beginning of the sixteenth century, it was reworked several times before reaching publication. Castiglione made the decision to have it printed only in the final years of his life, when he was papal nuncio in Spain. The text had had a wide manuscript circulation and the author was worried about the alterations it may have undergone during the many passages from one reader to another and from one copy to another. So, finally, in 1528 he sent a letter to Giovanni Battista Ramusio, then Chancellor of the Republic of Venice, asking him to take care of the publication of the volume. For this venture, Castiglione wanted the press of the most prestigious typographer in town, Giovanni Francesco Torresani, the heir of Aldus Manutius and Andrea Torresani.

Ramusio had previously received a manuscript copy of the Cortegiano from Bartolomeo Navagero, Andrea Navagero's brother, upon his return from Spain. Though at first hesitant, since publishing a book in Italian vernacular was unusual for the company, Torresani eventually agreed to take on the commitment, on the condition that the text be revised by a someone of his choice; this person would be Giovanni Francesco Valier, whose corrections, however, have proven to not always be the most scrupulous.

The Cortegiano was an immediate bestseller and by the end of the century had already attained the status of a classic. It was reprinted several times and translated into Spanish, French, English, German, Dutch, Polish, and Latin. In October 1528, six months after the publication of the first edition, Filippo Giunta's heirs printed a pocket edition of the work, the first in small format, in Florence. The demand for the book increased rapidly and, in the years immediately following 1528, publishers started to compete for the title, boasting of the correctness of their prints. The title pages of two Venetian editions of 1538 declared their respective texts to be “newly corrected”; in 1547, Aldus's house responded with an edition that was said to have been collated with the author's autograph manuscript. Gabriel Giolito de' Ferrari entered relatively late in this competition, in 1552, when he charged his editor and proof reader Ludovico Dolce to revise the text.

The Book of the Courtier, one of the most celebrated and influential texts of the Italian Renaissance, is written in dialogue form. The scene takes place in Urbino and lasts four evenings. The interlocutors are some of the most illustrious personalities of the time, including the Duchess Elisabetta Gonzaga, Emilia Pio, Cesare Gonzaga (the author's cousin), Ludovico di Canossa, the Cardinal Bibbiena, Federico and Ottaviano Fregoso, Pietro Bembo, Giuliano de' Medici, Gaspare Pallavicino, and Bernardo Accolti (called Unico Aretino).

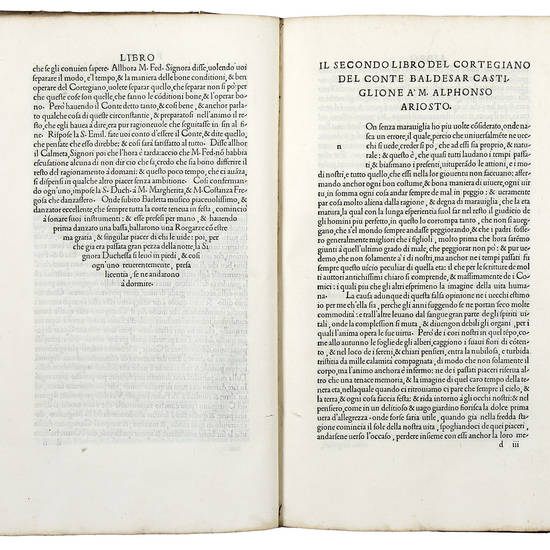

In the first book, dedicated to the education of a gentleman, the author addresses the topic of language most suitable for a courtier. Unlike other leading theorists of the Italian vernacular, such as P. Bembo, G.G. Trissino, and C. Tolomei, Castiglione here is not interested in language as a literary device, but rather as an attribute of a certain social condition and a fundamental element of the courtier's discipline and behavior within the organized life of the court. Castiglione therefore rejects any archaism and mannerism, and proposes a language that is spontaneous and close to the spoken language, while also resisting being naive and popular. Castiglione's linguistic model is thus reflective of the kind of linguistic naturalism that developed in the highly codified life of the Italian Renaissance courts.

The second book describes the qualities required by a courtier as a man of society, including self-control. As Castiglione explains, he must fully develop this in all its individual faculties: weapon mastery, proficiency in games, a deep knowledge of arts and literature, brilliant and ironic conversation, and the avoidance of all affectation. In the third book, Giuliano de' Medici and the misogynist Gaspare Pallavicino discuss the role of women at court. Finally, the fourth book deals with the relationship between the courtier and the prince, and contains a dissertation by Bembo on the doctrine of Platonic love.

As a manual of good manners and a summa of courtly etiquette, in addition to its pleasant dialogic form, the Cortegiano, had an enormous impact on European culture, influencing not only successive treaties on the subject, but also poetry and theatre more generally. Castiglione first outlined the characteristics and social obligations of the figure of the perfect man of court, confident, humorous and self-sufficient; a figure that in Spain was named ‘caballero', in France ‘honnête homme', and in England, the country where his influence was even greater, the gentleman (O. Zorzi Pugliese, Castiglione's ‘The Book of the Courtier' (Il ibro del cortegiano). A classic in the making, Napoli, 2008).

Born in Casatico (Mantua) in 1478, Baldassare Castiglione studied in Milan at the school of Giorgio Merula and Demetrio Calcondila. After the death of his father in 1499, he returned to Mantua and entered the service of Francesco Gonzaga. Between 1504 and 1513 he was at the court of Urbino, which then also housed Pietro Bembo. In Urbino, Castiglione first served Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, and then his successor, Francesco Maria della Rovere.

In 1513 he was sent to Rome as a diplomatic agent. At the court of Leo X he met Bembo again and made the acquaintance of Cardinal Bibbiena, for whom he wrote the prologue to the celebrated comedy Calandra (1513), as well as the great artist Raphael, who produced a splendid portrait of him and introduced him to the painter's circles. In 1516 he returned to Mantua and married Ippolita Torelli. After just four years he became a widower and in 1521 he embraced ecclesiastical life. In 1524 Castiglione was appointed papal nuncio in Spain. After the Sack of Rome in 1527, the pope accused him of mismanaging relations with the emperor, but he was soon after rehabilitated. He died in Toledo on February 8, 1529.

Politician, diplomat, man of arms and letters, Castiglione also wrote a famous pastoral eclogue, the Tirsi (Venice, 1553), and various Latin and vernacular poems that, after his death, appeared scattered among many 16th-century poetic anthologies (cf. P. Burke, The Fortunes of the ‘Courtier'. The European Reception of Castiglione's ‘Cortegiano', Cambridge, 1995).

Edit 16, CNCE10073; Adams, C-931; A.A. Renouard, Annales de l'Impremerie des Alde, Paris, 1834, p. 131, no. 4; Gamba, no. 294; Printing and the Mind of Man, no. 59; Ahmanson-Murphy, 328.

[7142]