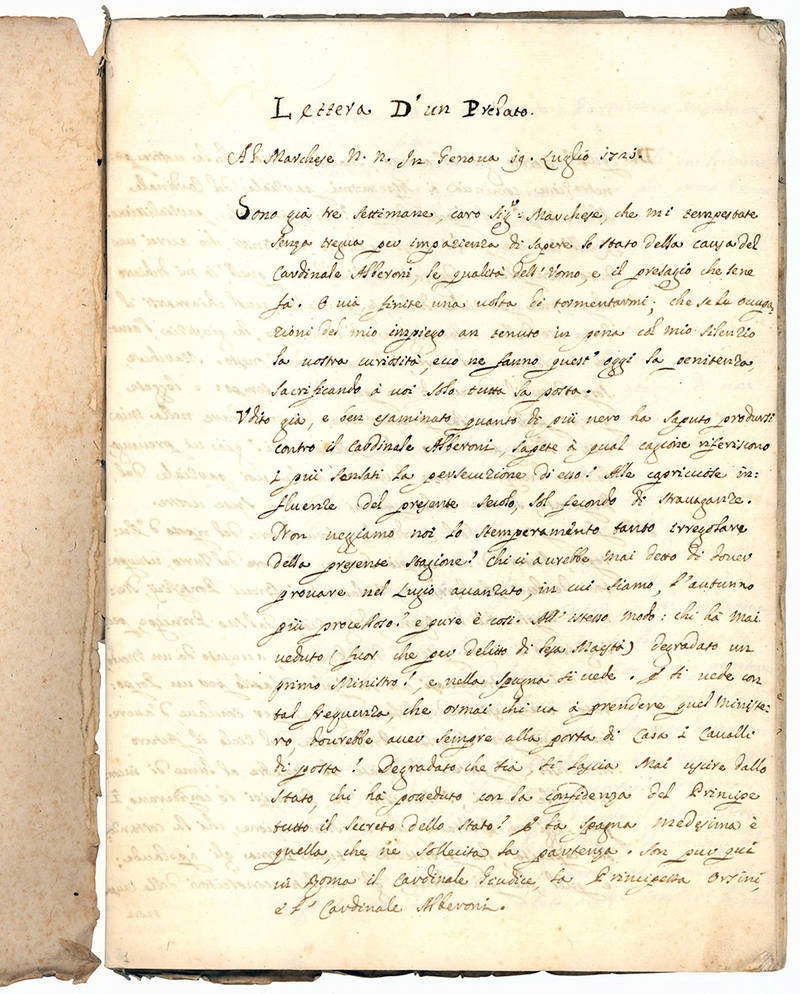

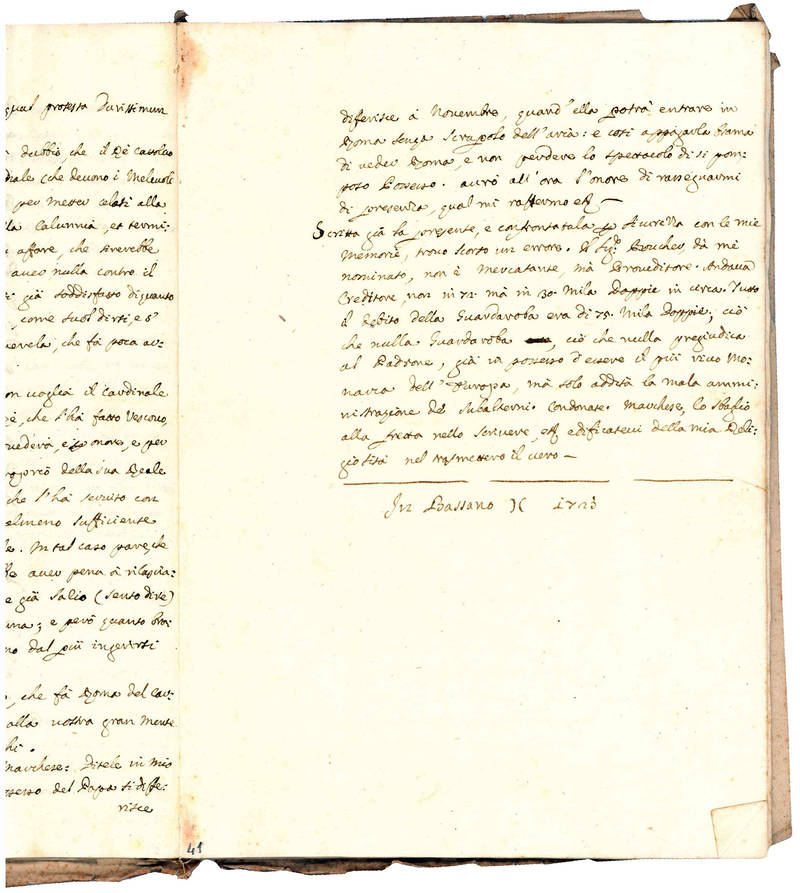

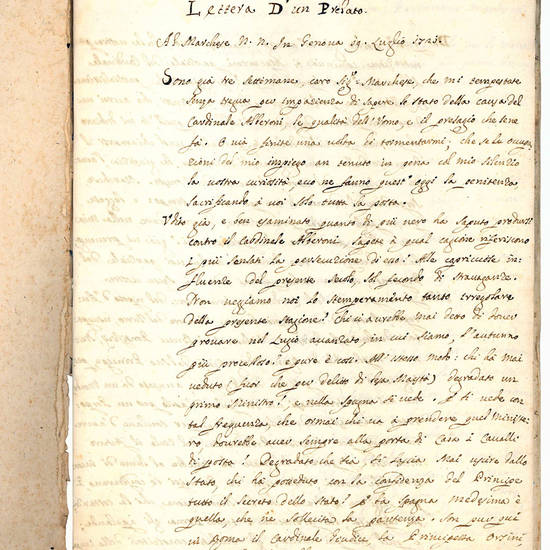

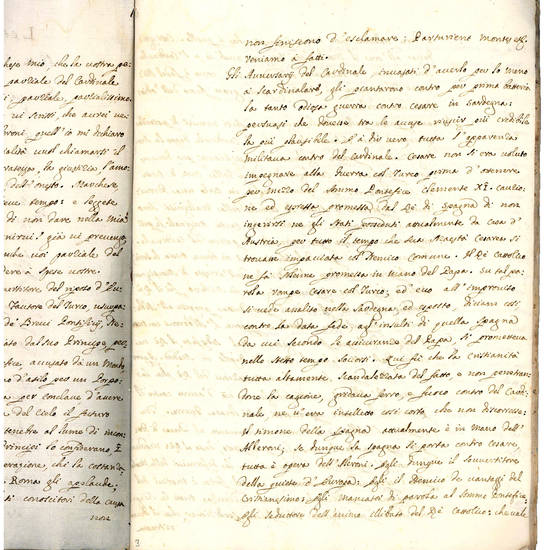

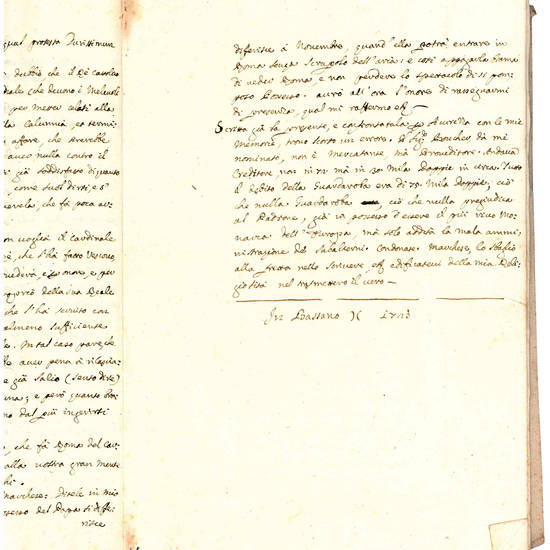

Folio (288x204 mm). The manuscript consists of a single quire of 42 leaves, of which only the first 20 leaves and the recto of the 21st contain the text; all the others are blank. Contemporary wrappers (some losses to spine and back panel). A very good copy.

Manuscript copy (a printed edition, now very rare, appeared without typographical notes around 1721) of this text concerning the cause of Cardinal Giulio Alberoni. The anonymous author wrote it in epistolary form, as fictitious as ever, where the writer (a not specified Prelate) anticipates the questions of the impatient (also not identified) Marquis who has been pestering him for three weeks to know where the cardinal's cause stands.

But what cause are we talking about? How is it possible that one of the most powerful men and skilled diplomats of his time had stumbled upon two lawsuits, one in the Vatican and one at the Spanish court!

Alberoni was of very humble origins, the son of the ortolan of a religious institute in Fiorenzuola in the duchy of Parma; an ortolan himself, he attracted the local bishop's attention for his lively intelligence. He was then allowed to take his vows and was given a position as canon in the cathedral chapter.

Alberoni's career was very rapid. During the War of the Spanish Succession (1717-20), he entered the service of the Duke of Bourbon Vendôme, commander of the French troops in Italy. Arriving in France with the duke, the latter introduced him to Louis XIV and was able to earn him a pension. Vendôme also made him his personal secretary and with his help restored Philip V to the Spanish throne. When the duke died while the two were in Spain, thanks to his reputation Alberoni was appointed as consular agent of the duchy of Parma at the Spanish court. He soon became one of the king's favorites, and after the death of the queen (M.L. of Savoy), he concluded his first diplomatic masterpiece by marrying Philip V to Elisabetta Farnese, niece of the duke of Parma. He was then appointed prime minister, duke and grandee of Spain. In 1717 Clement XI created him cardinal.

Once he became prime minister, Alberoni found Spain in a miserable state. “He found all in ruins the Royal Company, the commerce, the Navy, India abandoned already for 30 years to the rapacity of foreigners. No Troops, no Arms, no Artillery; no money either that came in from India, and went out in great abundance from Spain, which deprived of manufactures needed to get everything from outside (i.e., from abroad)”.

According to the present report, King Charles II (1665-1700) could at times not even leave his palace or go on vacation, and he even struggled to have lunch. The queen had ordered carriages from Paris, which were not delivered as they were not paid, and, most curiously indeed, the coachmen went on a “strike”, retreating to a church.

In the scant five years of his premiership (from 1715 until December 1719) Alberoni initiated or undertook numerous industrial, agricultural and commercial ventures, awakening Spain from a torpor that had lasted since 1681 (the year in which the ‘Siglo de oro' is conventionally brought to an end). He began to radically reform the complicated and cumbersome Spanish bureaucracy, which was favoring a parasitic class that ranged from ushers to the highest magistracies. He introduced the finest “table linen” into Madrid, bringing in skilled workers from Holland to teach 400 Spanish women workers to weave with Dutch mastery.

After the defeat suffered against the Quadruple Alliance, Alberoni, who had advocated that war so much, although he considered it untimely, became the scapegoat of all evils. After the naval defeat of Capo Passero (1718), in which the Spanish fleet that had cost the cardinal so much effort and commitment was almost totally annihilated by the English fleet while attempting to conquer Sicily, at the negotiating table the four powers demanded that Alberoni be removed from the Spanish government (Treaty of The Hague of February 20, 1720). At the end of 1719 Alberoni was relieved of all duties and invited to leave Spain. A difficult period followed for him, attacked by his enemies both at the Spanish court and in Rome; he, however, as proof of his tenacity, nevertheless participated in the conclave in which Innocent XIII was elected (May 8, 1721).

This Letter is actually not so much a report on Alberoni's past, present, and future life, but rather an apology commissioned or perhaps written by the cardinal himself with the purpose to be read by his future inquisitors. If we accept for good the date of the Letter (July 19, 1721), we see that within a few weeks Alberoni would contribute to the election of Innocent XIII and, in the following years, he would manage to rehabilitate himself at the Roman court. In 1735 he was appointed legate in Romagna. Alberoni died in Piacenza at the age of 88, leaving 600,000 scudi for the erection of the famous college that still bears his name.

[10736]